You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Understanding and using live sound equipment

- Thread starter simoncroft

- Start date

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Upright pianos

When the venue's budget and/or the space on stage does not permit the real estate occupied by a grand piano, the traditional alternative is the upright piano. There was a time when every pub in Great Britain had one of these acoustic gems. Usually, the action was awful, the tuning was slightly flatter on the middle keys where Uncle Albert bashed out Danny Boy, and the hammers were so hardened with wear it sounded as if someone had put tin tacks in them.

Those instruments are best regarded as 'furniture' to be pushed into the corner and ignored. Seriously, there are any number of electronic keyboards that would be a better choice. However, there are some venues that still have a well-maintained upright. Small jazz pubs in particular have to provide an instrument that is up to the demands of the idiom, so let's hope you're working with one of those.

There's a good article on recording upright pianos here: Q. How do you record Upright Piano?

However, we really concerned with miking in a live situation, so I'll pull out a nugget here.

Paul: For starters, before setting the mics up, I'll always try to take off the casing of the piano; usually the lid and the section of front panel directly above the keyboard, but also the panel above the pedals. Once you've taken these off, the whole thing will sound better, with fewer rattles and boxy colorations. Also, it will be a lot easier to place the mics.

When the venue's budget and/or the space on stage does not permit the real estate occupied by a grand piano, the traditional alternative is the upright piano. There was a time when every pub in Great Britain had one of these acoustic gems. Usually, the action was awful, the tuning was slightly flatter on the middle keys where Uncle Albert bashed out Danny Boy, and the hammers were so hardened with wear it sounded as if someone had put tin tacks in them.

Those instruments are best regarded as 'furniture' to be pushed into the corner and ignored. Seriously, there are any number of electronic keyboards that would be a better choice. However, there are some venues that still have a well-maintained upright. Small jazz pubs in particular have to provide an instrument that is up to the demands of the idiom, so let's hope you're working with one of those.

There's a good article on recording upright pianos here: Q. How do you record Upright Piano?

However, we really concerned with miking in a live situation, so I'll pull out a nugget here.

Paul: For starters, before setting the mics up, I'll always try to take off the casing of the piano; usually the lid and the section of front panel directly above the keyboard, but also the panel above the pedals. Once you've taken these off, the whole thing will sound better, with fewer rattles and boxy colorations. Also, it will be a lot easier to place the mics.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

I'd suggest a modified version of the first miking scheme Sound on Sound shows and remove only the top panel, revealing the part of the strings where the hammers strike.

Forget about miking underneath the keys: it's a complication you can live without, and you just know the piano player is going to kick one of the stands now and again.

With that in mind, I'd place two booms stands behind the piano, bring the booms over the top, and point a pair of cardioid mics (condensers, or good quality dynamics) in the approximate positions shown in the picture. The closer you get those mics, the more level you can achieve without spill or feedback, but the further away they are, the less chance you'll a dip in level right in the middle. If that happens, you'll need to move the mics closer together.)

One more thing about pianos before we move on. Just like acoustic guitars, acoustic pianos can and will start to exhibit all sorts of unwanted sympathetic resonances and 'wolf notes' if you subject them to loud notes and vibrations from other instruments.

I have seen a number of approaches to combating this problem, ranging from suspending mics inside the piano and keeping all lids and panels shut, to bizarre arrangements involving sandbags at the back to increase the acoustic isolation.

In my opinion, these are doomed to failure, in as much as they compromise the sound of the piano. Unless you really are playing a major festival with Coldplay, I'd prefer to tell the band they're starting to drown out the piano player and need to back off the volume on stage. Whether that makes the band resent each other, or me, isn't really my problem.

Next post vocal mics, including radio mics.

Forget about miking underneath the keys: it's a complication you can live without, and you just know the piano player is going to kick one of the stands now and again.

With that in mind, I'd place two booms stands behind the piano, bring the booms over the top, and point a pair of cardioid mics (condensers, or good quality dynamics) in the approximate positions shown in the picture. The closer you get those mics, the more level you can achieve without spill or feedback, but the further away they are, the less chance you'll a dip in level right in the middle. If that happens, you'll need to move the mics closer together.)

One more thing about pianos before we move on. Just like acoustic guitars, acoustic pianos can and will start to exhibit all sorts of unwanted sympathetic resonances and 'wolf notes' if you subject them to loud notes and vibrations from other instruments.

I have seen a number of approaches to combating this problem, ranging from suspending mics inside the piano and keeping all lids and panels shut, to bizarre arrangements involving sandbags at the back to increase the acoustic isolation.

In my opinion, these are doomed to failure, in as much as they compromise the sound of the piano. Unless you really are playing a major festival with Coldplay, I'd prefer to tell the band they're starting to drown out the piano player and need to back off the volume on stage. Whether that makes the band resent each other, or me, isn't really my problem.

Next post vocal mics, including radio mics.

Amp Mad Scientist

Ambassador of Heresy

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

If that was the one on Reverb from Tone House, is it you who has just bought it? I was actually expecting it to be more expensive, TBH.I just discovered White instruments 4303 1/6 octave EQ

View attachment 104085

I'm in love now.

I must have it ! It WILL be mine.

I'm dreaming of a WHITE 4303 Christmas.

They actually make a "cut only" version, which is my preference. So now you know what to get me for Christmas.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Miking Vocals

One of the problems when it comes to miking vocals is similar to the one with drums – everyone's seen it done and most of us have had a go at it – so everyone and their uncle thinks they know all about it. Quite often, some of the things they think they 'know' are based on misconceptions, not facts.

Now, you can write a perfectly good primer on miking drums or pianos without once mentioning the musician, except perhaps for strategies for stopping them accidentally hitting the mics or stands. It would be careless of me to talk about miking vocals without flagging up some of the things singers do that engineers find very hard to fix. Here are a few that are best avoided.

Cupping the mic. Some singers seem to do this because they think it reduces feedback, others seem to think it makes them sound better. I hope I can convince you, and everyone else, that the opposite is the case in both instances.

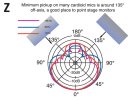

Going back to diagram Z, we have a polar plot for a typical cardioid mic at three different frequencies, along with suggested positions for on-stage monitor wedges. As soon as you cup a hand over the mic, those polar plots go out of the window and the mic becomes something closer to omni-directional. While cupping a hand over the top of the mic does this the worst, the Death Metal 'grab the top of the mic with both hands before making vomiting noises' technique does not fare much better.

(At the risk of going too off topic, I should also mention that sax, trumpet and other instrument bells do something very similar. This gets into a destructive cycle if the player starts to hog the mic in order to be louder, as the engineer is forced to reduce the monitor volume to minimize the risk of feedback, making the player hog the mic even more, meaning the engineer has to...)

Also, the frequency plot becomes a work of fiction once a hand is cupped over a mic. Why? Well, you wouldn't stick a bucket over your head and expect everything to sound the same, would you?

Suffice to say that if the monitor wedge is in the 180° position, the chances of cupping the mic causing feedback is increased. This is because all directional mics have a 'lobe' at 180°, which gets a lot bigger thanks to that hand, horn bell or other mechanical obstruction. It's worth noting that mics with a hypercardioid pickup pattern – while generally more directional than cardioid mics – have a bigger lobe at 180° off-axis. This makes it even more essential that wedge monitos are not pleaced directly behing the mic.

Getting too close/far away. Mic munching and clear diction do not go together! Apart from the fact that I defy anyone to produce clearly intelligible words with a metal grille pressed against their lips.

There is also 'proximity effect' to consider. Due to the laws of physics, the closer a singer, or other sound source, gets to a directional mic (not omni), the bigger the boost to the low frequencies. Some singers exploit this effect a little to make their voice sound more intimate and rounded, but once we get within an inch or so off the mic, things can get muddy and indistinct.

The proximity effect is less noticeable on female voices, so it is a paradox they are usually the most likely to get too far away from the mic. One very obvious problem, especially if the singer is not a loud one, is that the engineer has to significantly increase the input gain, and the likelihood of feedback with it.

But there is a point, somewhere about a foot away, where mics are particularly prone to plosive plops. (Nice turn of phrase, huh?) Take one shy, quiet, female singer, make the very reasonable assessment that a Shure SM57 will suit her voice, and prepare for a problematic time if she treats the mic as if the last singer had really bad breath.

The ideal distance from a vocal mic is somewhere around six inches, but some singers don't even stick to a constant distance. This brings us to what I call...

Cabaret singer technique. Some singers, usually of the sequinned jacket persuasion, have developed bad habits when it comes to handheld mics. They pull the mic away from their mouths, or move it closer, as some sort of manual level control. I once heard a comedian, who was presumably trying to disguise the fact he couldn't really sing, do this so compulsively at the start of every word that it sounded as if someone had set up a compressor with all the wrong settings as a 'what not to do' demonstration.

Next topic: what characteristics should we look for in a vocal mic?

One of the problems when it comes to miking vocals is similar to the one with drums – everyone's seen it done and most of us have had a go at it – so everyone and their uncle thinks they know all about it. Quite often, some of the things they think they 'know' are based on misconceptions, not facts.

Now, you can write a perfectly good primer on miking drums or pianos without once mentioning the musician, except perhaps for strategies for stopping them accidentally hitting the mics or stands. It would be careless of me to talk about miking vocals without flagging up some of the things singers do that engineers find very hard to fix. Here are a few that are best avoided.

Cupping the mic. Some singers seem to do this because they think it reduces feedback, others seem to think it makes them sound better. I hope I can convince you, and everyone else, that the opposite is the case in both instances.

Going back to diagram Z, we have a polar plot for a typical cardioid mic at three different frequencies, along with suggested positions for on-stage monitor wedges. As soon as you cup a hand over the mic, those polar plots go out of the window and the mic becomes something closer to omni-directional. While cupping a hand over the top of the mic does this the worst, the Death Metal 'grab the top of the mic with both hands before making vomiting noises' technique does not fare much better.

(At the risk of going too off topic, I should also mention that sax, trumpet and other instrument bells do something very similar. This gets into a destructive cycle if the player starts to hog the mic in order to be louder, as the engineer is forced to reduce the monitor volume to minimize the risk of feedback, making the player hog the mic even more, meaning the engineer has to...)

Also, the frequency plot becomes a work of fiction once a hand is cupped over a mic. Why? Well, you wouldn't stick a bucket over your head and expect everything to sound the same, would you?

Suffice to say that if the monitor wedge is in the 180° position, the chances of cupping the mic causing feedback is increased. This is because all directional mics have a 'lobe' at 180°, which gets a lot bigger thanks to that hand, horn bell or other mechanical obstruction. It's worth noting that mics with a hypercardioid pickup pattern – while generally more directional than cardioid mics – have a bigger lobe at 180° off-axis. This makes it even more essential that wedge monitos are not pleaced directly behing the mic.

Getting too close/far away. Mic munching and clear diction do not go together! Apart from the fact that I defy anyone to produce clearly intelligible words with a metal grille pressed against their lips.

There is also 'proximity effect' to consider. Due to the laws of physics, the closer a singer, or other sound source, gets to a directional mic (not omni), the bigger the boost to the low frequencies. Some singers exploit this effect a little to make their voice sound more intimate and rounded, but once we get within an inch or so off the mic, things can get muddy and indistinct.

The proximity effect is less noticeable on female voices, so it is a paradox they are usually the most likely to get too far away from the mic. One very obvious problem, especially if the singer is not a loud one, is that the engineer has to significantly increase the input gain, and the likelihood of feedback with it.

But there is a point, somewhere about a foot away, where mics are particularly prone to plosive plops. (Nice turn of phrase, huh?) Take one shy, quiet, female singer, make the very reasonable assessment that a Shure SM57 will suit her voice, and prepare for a problematic time if she treats the mic as if the last singer had really bad breath.

The ideal distance from a vocal mic is somewhere around six inches, but some singers don't even stick to a constant distance. This brings us to what I call...

Cabaret singer technique. Some singers, usually of the sequinned jacket persuasion, have developed bad habits when it comes to handheld mics. They pull the mic away from their mouths, or move it closer, as some sort of manual level control. I once heard a comedian, who was presumably trying to disguise the fact he couldn't really sing, do this so compulsively at the start of every word that it sounded as if someone had set up a compressor with all the wrong settings as a 'what not to do' demonstration.

Next topic: what characteristics should we look for in a vocal mic?

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

When I posted the above somewhere else on-line, one reader who knows his stuff commented that cowboy hats, and other wide-brimmed headwear can cause similar problems to singers cupping the mic, saxes getting too close etc. The first person to make me aware of this was mixing FoH for Elton John. Elton likes his monitors head-crushingly loud, and on this tour, he was wearing a straw boater. (Please see pic below of man looking like a right nob.) Anyway, a lot of sound was reflecting off the brim, causing various random changes to the performance of the mic.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

What makes for a great vocal mic?

I suppose most people's immediate reaction to that question would be something like: “Obviously, it's got to sound really good.” Delivering that seeming simple requirement is more complicated than it might appear, because it actually breaks down into a whole wish list, each of which demands a number of design solutions.

Frequency response. While for recording applications, we would probably want the frequency response of our microphones to be as close to completely linear as possible, many of the world's most successful stage vocal mics, are anything but, as this plot for a Shure SM58 illustrates. Notice how the frequency response rolls off below 100Hz and 9kHz, but peaks significantly in much of the 4kHz-8kHz vocal range. This means the response is tailored to diminish the unwanted parts of the frequency spectrum and to help the voice 'cut through' the rest of the band.

Polar pattern. Diagram Z above shows a typical cardioid and this is the favored polar pattern, as it offers a high degree of immunity from feedback, providing speakers are placed with care and volume levels are kept in check.

There are 'hyper-cardioid' mics that exhibit even greater attenuation at 90° off-axis, but I would argue that this isn't a 'free lunch'. For one thing, the 'lobe' at 180° off-axis will be larger, meaning it could actually be more prone to feedback if care is not taken over monitor placement. For another, it means the singer needs to be disciplined about staying on-axis.

Personally, I've tended to find hyper-cardioid stage mics can sound somewhat lifeless. In fact, the only one I really took to was the long discontinued AKG D330-BT, which sounds excellent. Unusually, it has an adjustable bass roll-off and adjustable treble contour. These sometimes sell for surprisingly little and are well worth seeking out. They also benefit from...

Effective shock mounts and pop filters. If you take a look at large-capsule condenser mic on vocal duties, you'll usually find the mic is mounted in an elasticated cradle-mount to protect it from an vibration transmitted through the floor, and an external pop shield between the singer and the delicate capsule of the mic. Those are not arrangements than lend themselves to a handheld mic!

Therefore, the way the capsule is mounted inside the casing of a stage vocal mic is critical to keeping rumble and unwanted impact noise out of the audio chain. This usually involves the capsule being mounted on some sort of neoprene arrangement to isolate it from the metal casing.

The pop shield is, of course, internal and is formed by a combination a shaped metal mesh and an inner layer of foam. These design features also help to protect the mic from damage in more extreme circumstances, such as being dropped, hit by a drum stick, or in the case of John Ottway, head-butted.

I suppose most people's immediate reaction to that question would be something like: “Obviously, it's got to sound really good.” Delivering that seeming simple requirement is more complicated than it might appear, because it actually breaks down into a whole wish list, each of which demands a number of design solutions.

Frequency response. While for recording applications, we would probably want the frequency response of our microphones to be as close to completely linear as possible, many of the world's most successful stage vocal mics, are anything but, as this plot for a Shure SM58 illustrates. Notice how the frequency response rolls off below 100Hz and 9kHz, but peaks significantly in much of the 4kHz-8kHz vocal range. This means the response is tailored to diminish the unwanted parts of the frequency spectrum and to help the voice 'cut through' the rest of the band.

Polar pattern. Diagram Z above shows a typical cardioid and this is the favored polar pattern, as it offers a high degree of immunity from feedback, providing speakers are placed with care and volume levels are kept in check.

There are 'hyper-cardioid' mics that exhibit even greater attenuation at 90° off-axis, but I would argue that this isn't a 'free lunch'. For one thing, the 'lobe' at 180° off-axis will be larger, meaning it could actually be more prone to feedback if care is not taken over monitor placement. For another, it means the singer needs to be disciplined about staying on-axis.

Personally, I've tended to find hyper-cardioid stage mics can sound somewhat lifeless. In fact, the only one I really took to was the long discontinued AKG D330-BT, which sounds excellent. Unusually, it has an adjustable bass roll-off and adjustable treble contour. These sometimes sell for surprisingly little and are well worth seeking out. They also benefit from...

Effective shock mounts and pop filters. If you take a look at large-capsule condenser mic on vocal duties, you'll usually find the mic is mounted in an elasticated cradle-mount to protect it from an vibration transmitted through the floor, and an external pop shield between the singer and the delicate capsule of the mic. Those are not arrangements than lend themselves to a handheld mic!

Therefore, the way the capsule is mounted inside the casing of a stage vocal mic is critical to keeping rumble and unwanted impact noise out of the audio chain. This usually involves the capsule being mounted on some sort of neoprene arrangement to isolate it from the metal casing.

The pop shield is, of course, internal and is formed by a combination a shaped metal mesh and an inner layer of foam. These design features also help to protect the mic from damage in more extreme circumstances, such as being dropped, hit by a drum stick, or in the case of John Ottway, head-butted.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Radio Mics – are you receiving me?

When you're playing a massive festival and there's a vast audience to entertain, not to mention a considerable amount of on-stage real estate to fill, radio mics and wireless guitar systems make it a lot easier to work the crowd and the stage area. In the cramped confines of a backstreet bar, the argument for wireless systems is somewhat weaker, but bands like them, partly because it puts them up there with the big boys, visually, anyway. Whether the audible results hit the same dizzying heights is down to a number of factors, which I'll set out as simply as I can.

It's worth mentioning at the point that IEM (In Ear Monitoring) systems are invariably wireless, because the potential for disaster on stage would be too great with wired ear-pieces!

The first thing to understand as a wireless user is you are not alone! Radio stations, TV stations, emergency services, taxi companies, other venues, cell phones, and your bandmates are all likely to transmitting at the same time in the same space. In order to prevent chaos, and the possibility of interference to ambulances and other vital services, the regulatory body in each territory decides which frequency bands can be used for what type of application.

The regulatory body in the US is the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) and in the UK it is Ofcom (the official body for communications). Their guidelines for wireless microphone operation can be found here: Operation of Wireless Microphones

https://www.ofcom.org.uk/manage-you...cences/pmse/pmse-technical-info/mics-monitors

Be aware that you will need a license to transmit in many instances. “Failure to comply with FCC rules by unlawfully operating wireless mics or devices in the 600 and 700 spectrum bands may result in fines or additional criminal penalties.” You have been warned!

NB 1 – As new technologies emerge (digital TV, new generations of cell phone etc etc), the regulatory bodies change the rules from time-to-time to make the most efficient allocation of the finite bandwidth. This isn't a problem when buying a new system form an established brand, but it's worth checking exactly what you're getting into before splashing the cash on a pawnshop prize.

NB 2 – You can't mix and match brands in the wireless world, so just because a Shure mic is on the same frequency as an AKG, it doesn't mean they will place nicely together. There are a number of reasons for this, of which one is the use of 'compander' circuits. These compress the signal before transmitting, then expand it again once it is received, thereby maximizing the dynamic range of the signal in what is usually a very restricted radio bandwidth. These circuits are proprietary, and are not compatible.

When you're playing a massive festival and there's a vast audience to entertain, not to mention a considerable amount of on-stage real estate to fill, radio mics and wireless guitar systems make it a lot easier to work the crowd and the stage area. In the cramped confines of a backstreet bar, the argument for wireless systems is somewhat weaker, but bands like them, partly because it puts them up there with the big boys, visually, anyway. Whether the audible results hit the same dizzying heights is down to a number of factors, which I'll set out as simply as I can.

It's worth mentioning at the point that IEM (In Ear Monitoring) systems are invariably wireless, because the potential for disaster on stage would be too great with wired ear-pieces!

The first thing to understand as a wireless user is you are not alone! Radio stations, TV stations, emergency services, taxi companies, other venues, cell phones, and your bandmates are all likely to transmitting at the same time in the same space. In order to prevent chaos, and the possibility of interference to ambulances and other vital services, the regulatory body in each territory decides which frequency bands can be used for what type of application.

The regulatory body in the US is the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) and in the UK it is Ofcom (the official body for communications). Their guidelines for wireless microphone operation can be found here: Operation of Wireless Microphones

https://www.ofcom.org.uk/manage-you...cences/pmse/pmse-technical-info/mics-monitors

Be aware that you will need a license to transmit in many instances. “Failure to comply with FCC rules by unlawfully operating wireless mics or devices in the 600 and 700 spectrum bands may result in fines or additional criminal penalties.” You have been warned!

NB 1 – As new technologies emerge (digital TV, new generations of cell phone etc etc), the regulatory bodies change the rules from time-to-time to make the most efficient allocation of the finite bandwidth. This isn't a problem when buying a new system form an established brand, but it's worth checking exactly what you're getting into before splashing the cash on a pawnshop prize.

NB 2 – You can't mix and match brands in the wireless world, so just because a Shure mic is on the same frequency as an AKG, it doesn't mean they will place nicely together. There are a number of reasons for this, of which one is the use of 'compander' circuits. These compress the signal before transmitting, then expand it again once it is received, thereby maximizing the dynamic range of the signal in what is usually a very restricted radio bandwidth. These circuits are proprietary, and are not compatible.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Choices, choices

Enough with the dire warnings, how do you choose the right radio system for you? The first thing to do is define your requirement. For instance, if you told me you needed to run 16 radio mics for a big-budget stage musical, I'd point you at a very different to one you might use for your karaoke. Equally though, if you think you are likely to want to run more than one mic in future, you save money and have a more elegant solution if you buy a multichannel system from the off, rather than buying another single channel system down the line.

I was going to write several more pages on this topic, but there are a lot of useful videos on Yout Tube that cover the basics. This one is naturally quite sales orintated but still onformative:

That leaves me free to give you some bullet-point observations:

• VHF versus UHF. You get more range and a greater choice of operating frequencies with Ultra High Frequency systems. Very High Frequency systems can give good results, as long as you understand the limitations.

• Frequency agility. You can only have one transmitter per frequency within the transmitter's range. So if you have two singers in your act, the radio mics must be on different frequencies. But if you play at a festival, or next door to a stage show, you might find those frequencies are already in use. ' Frequency agility' means the system allows you to pick a new frequency that is free.

• Automatic Frequency Selection. It's a nice time-saver if you have a lot of mics to set up, but it comes at a price. For smaller configurations, which don't need changing too often, you can live without it.

• Diversity. This doesn't mean the system is suitable for Country and Western. It means there are two separate receivers, and the system always switches to the one with the best reception. It's well worth it if you can afford it, but make sure you get a 'true diversity' system, not just one with two aerials.

Tip 1 – Just like Wi-Fi, radio mics don't work two well through solid obstructions, doubly so if there is metal involved. Try to maintain a clear line-of-site between the transmitter and the receiver. Also, it's best not to operate a receiver right next to a large metal surface – like a mixing desk or the flight case it came in.

Tip 2 – Always start a gig with new batteries – or freshly recharged ones if you'd prefer not to cause unneccesary waste. Radio mics have an uncanny knack of dying at the worst possible moment if you don't take this simple precaution. ("And now, a speech from the bride's father. Sorry, can anyone actually hear me?...")

Enough with the dire warnings, how do you choose the right radio system for you? The first thing to do is define your requirement. For instance, if you told me you needed to run 16 radio mics for a big-budget stage musical, I'd point you at a very different to one you might use for your karaoke. Equally though, if you think you are likely to want to run more than one mic in future, you save money and have a more elegant solution if you buy a multichannel system from the off, rather than buying another single channel system down the line.

I was going to write several more pages on this topic, but there are a lot of useful videos on Yout Tube that cover the basics. This one is naturally quite sales orintated but still onformative:

That leaves me free to give you some bullet-point observations:

• VHF versus UHF. You get more range and a greater choice of operating frequencies with Ultra High Frequency systems. Very High Frequency systems can give good results, as long as you understand the limitations.

• Frequency agility. You can only have one transmitter per frequency within the transmitter's range. So if you have two singers in your act, the radio mics must be on different frequencies. But if you play at a festival, or next door to a stage show, you might find those frequencies are already in use. ' Frequency agility' means the system allows you to pick a new frequency that is free.

• Automatic Frequency Selection. It's a nice time-saver if you have a lot of mics to set up, but it comes at a price. For smaller configurations, which don't need changing too often, you can live without it.

• Diversity. This doesn't mean the system is suitable for Country and Western. It means there are two separate receivers, and the system always switches to the one with the best reception. It's well worth it if you can afford it, but make sure you get a 'true diversity' system, not just one with two aerials.

Tip 1 – Just like Wi-Fi, radio mics don't work two well through solid obstructions, doubly so if there is metal involved. Try to maintain a clear line-of-site between the transmitter and the receiver. Also, it's best not to operate a receiver right next to a large metal surface – like a mixing desk or the flight case it came in.

Tip 2 – Always start a gig with new batteries – or freshly recharged ones if you'd prefer not to cause unneccesary waste. Radio mics have an uncanny knack of dying at the worst possible moment if you don't take this simple precaution. ("And now, a speech from the bride's father. Sorry, can anyone actually hear me?...")

Last edited:

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

There is a Second Edition of the Yamaha Sound Reinforcement Handbook available here: https://bgaudioclub.org/uploads/docs/Yamaha_Sound_Reinforcement_Handbook_2nd_Edition_Gary_Davis_Ralph_Jones.pdf

This is probably the best book on the subject in print. It isn't free and I would whole-heartedly recomend you to buy the current edition if you want to take a deep dive into the topic. However, the 2nd edition is widely available on-line from multiple sources if you just want a dip-in.

I gave my copy to a guy who was mixing the sound in a local bar. I met him a few years later, and he was working full-time as a sound engineer in the corporate sector, with clients including major car manufacturers, so I think he must have read that book very closely. That was more than 30 years ago!

This is probably the best book on the subject in print. It isn't free and I would whole-heartedly recomend you to buy the current edition if you want to take a deep dive into the topic. However, the 2nd edition is widely available on-line from multiple sources if you just want a dip-in.

I gave my copy to a guy who was mixing the sound in a local bar. I met him a few years later, and he was working full-time as a sound engineer in the corporate sector, with clients including major car manufacturers, so I think he must have read that book very closely. That was more than 30 years ago!

Last edited:

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

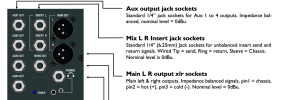

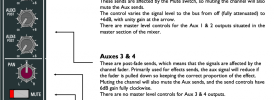

When I originally posted this material, someone messaged me to how to add a reverb unit to their mixing desk, so I'm repeating here in the hope that if anyone on The Tone Rooms needs to know, I can help them too. The desk in question is an Allen & Heath ZED 14, but the concepts are applicable to almost any mixer.

(Digital mixers typically have on-board effects, but it's quite possible you might also want to use some 'outboard' processors – which could even include plug-ins running on a laptop – or other computer. Although the way you achieve the routing will be slightly different to what I'm showing here, the underlying concepts are exactly the same.)

The first concept to understand is "send and return". That is to say, we're going to send a mix of our input channels to the external reverb (or whatever effect) unit, then return it to the main stereo mix, so that it can be heard as part of the Front of House sound.

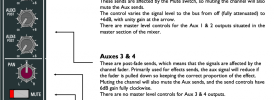

The place we start is the Aux mixes. On the ZED 14, the first two are Pre Fade. That is, they are used to create monitor mixes for the performers. These mixes are ahead of the channel faders, so if the FoH engineer changes any fader levels, it doesn't change the monitor mixes. If it did, it would be very distracting for the performers.

Aux 3 and 4 are Post Fade, which is what we want for an effects send mix. As the blurb says, we move the channel fader up or down, and the relative amount of effect stays the same. Otherwise, if we decided the vocal was a bit loud and pulled the fader, it would be quieter, but with more reverb. That isn't what we want.

(Digital mixers typically have on-board effects, but it's quite possible you might also want to use some 'outboard' processors – which could even include plug-ins running on a laptop – or other computer. Although the way you achieve the routing will be slightly different to what I'm showing here, the underlying concepts are exactly the same.)

The first concept to understand is "send and return". That is to say, we're going to send a mix of our input channels to the external reverb (or whatever effect) unit, then return it to the main stereo mix, so that it can be heard as part of the Front of House sound.

The place we start is the Aux mixes. On the ZED 14, the first two are Pre Fade. That is, they are used to create monitor mixes for the performers. These mixes are ahead of the channel faders, so if the FoH engineer changes any fader levels, it doesn't change the monitor mixes. If it did, it would be very distracting for the performers.

Aux 3 and 4 are Post Fade, which is what we want for an effects send mix. As the blurb says, we move the channel fader up or down, and the relative amount of effect stays the same. Otherwise, if we decided the vocal was a bit loud and pulled the fader, it would be quieter, but with more reverb. That isn't what we want.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

I know I've covered the role of pre and post fade aux mixes, but if I get asked the specifics of how to do something, it makes me realise I sometimes need to give more examples of how to achieve a particular result.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

On a mixing desk, any input is just 'an input'. That might sound like a stupid thing to say, but my point is this: just because a couple of inputs are labelled 'Stereo Effects Return' doesn't mean you can't use them for your background music player in the intervals. Equally, if you have a couple of spare channels on the main input section of the desk, there's nothing to say you can't use them as effects returns for your reverb, say.

Let's say we've used Aux 3 (Post Fade mix) to set our reverb mix, and sent it to our reverb unit via the Aux 3 out. There are a whole bunch of places we can return the L/R signals to. That includes a couple of Mono input channels. (See below.)

But why would you choose to do that? Well, for one thing, if you are using Aux 1 and 2 (Pre Fade) to send monitor mixes to the stage, you can now control how much reverb goes to the stage monitors. This is completely independent of the reverb levels going out Front of House. Let's say, you're using Input Channels 1 & 2 as your effects returns. The channel faders control how much effect goes to the main (FoH) mix. The Aux 1 and 2 rotaries control how much reverb goes to the stage monitors.

WARNING! If you go down this route, then turn up the Aux 3 send on Input Channels 1 & 2, you will create a feedback loop! The results will not be pretty. With great power comes great responsibility.

Let's say we've used Aux 3 (Post Fade mix) to set our reverb mix, and sent it to our reverb unit via the Aux 3 out. There are a whole bunch of places we can return the L/R signals to. That includes a couple of Mono input channels. (See below.)

But why would you choose to do that? Well, for one thing, if you are using Aux 1 and 2 (Pre Fade) to send monitor mixes to the stage, you can now control how much reverb goes to the stage monitors. This is completely independent of the reverb levels going out Front of House. Let's say, you're using Input Channels 1 & 2 as your effects returns. The channel faders control how much effect goes to the main (FoH) mix. The Aux 1 and 2 rotaries control how much reverb goes to the stage monitors.

WARNING! If you go down this route, then turn up the Aux 3 send on Input Channels 1 & 2, you will create a feedback loop! The results will not be pretty. With great power comes great responsibility.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

A few bullet points

Just a few tips based on my own mistakes in the past. In no particular order:

Just a few tips based on my own mistakes in the past. In no particular order:

- Once you have input gains set, try not to mess with them more than you really have to. If you change them mid-set, they’ll also alter the monitor mix levels.

- Don’t rush to EQ anything unless you feel there is a problem you need to fix. (To quote a very successful record producer who saw a junior engineer reaching for the EQ for no reason: “Listen, he’s a very good guitarist, playing an expensive guitar into an extremely nice microphone, and it’s a lovely day outside. Why are you trying to spoil it?”)

- Remember, your EQ settings will also affect the headroom through the mixer circuits. Best to avoid EQ boosts.

- Also, when you have a whole bunch of input channels going to a group/bus, use the AFL for that bus to see what the overall level is. It's easy to eat up all the headroom on a group, doubly so if you've fallen into the habit of excessive boost to get the sounds you're after. ('Gain staging' – meaning setting the optimimum signal level for each part of the audio chain – is arguably less important in the digital domain, but it's still good practice.)

- Solo/PFL are useful tools but try to confine them to your headphones and desk monitor, rather than running them to FoH. You might know why you’re doing it, but to anyone else in the room, it quickly gets irritating. NEVER send PFL to the main mix during a performance! (For this reason, it's best not to use PFL at all while an act is on, unless you are really sure you know what you're doing).

- No need to feel intimidated if you are running two or more monitor mixes from the FoH desk; simply keep all of them identical, then vary them if somebody asks for more ‘whatever’ in their mix.

- If you need a player to turn down their amp, give them a little more of their instrument in the monitors, so they’re not trying to play without hearing themselves.

- Don’t get carried away and blast the place out. The first time I set up a rig that could achieve a massive sound level without feedback, I was so proud of myself, I forgot to consider what the audience wanted to hear. So I blasted the place. I’ve seen people walk out if the volume is really excessive. (Not because of me BTW.)

- Vocal processing can be an important part of creating a polished live production, but don’t overdo it. Easy on those canyon-wide reverbs and delays!

- Remember to kill the vocal effects between numbers. If someone starts talking into a mic between numbers, it sounds ridiculous if they sound like they’re in the middle of a swimming pool, and sort of gives the game away.

- Do your main work in the sound check, so during the performance, you’re hopefully not ‘fiddling‘ with anything, just doing things like the point about vocal effects above. Also, you are not the act, you’re a technician, so there is no need to make a big show of handling the sound.

- At the other extreme, do not desert your post unless you really need a pee! Whether you are being paid or not, you’ll be letting down the act, the audience and the venue manager if you think your main priority is to drink beer, chat up the bar staff… when you should be at the console.

- If you want to be a sound ‘engineer’ you should take responsibility for at least the most basic levels of the way the equipment is maintained, and what to do if it fails. It is rare for anyone to get a soldering iron out during a gig, but you it will help you greatly if you can keep a level head and diagnose exactly where in the system your problem lies. Keeping calm and knowing you need to swap out a mic cable is a lot more effective than freaking out, then realizing the day after you could easily have fixed the situation.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Since I first started writing threads like this – around 10 years ago – live digital mixing consoles have fallen in price dramatically. Depending on how much physical hardware you want (ie – whether you're prepared to mix on a tablet, or demand 'real' controls), there does not have to be a massive difference in cost between analog and digital anymore. However, because they are different technologies, with different capabilities, it's not really possible to make like-for-like comparisons.

Three concepts that are especially useful in this 'new world' of digital mixing:

1. Assignable. Where we used to have a set of EQ knobs on every channel, it makes more sense in the digital domain to have one really nicely laid-out and versatile EQ section that you can assign to any channel. (Once we are up and running with this idea, there is no reason why all the input channel faders can't switch to being the graphic controllers for the system EQ, but let's blow our minds one step at a time!)

2. Automated. There is no reason we can't store a 'snapshot' of all the mixer settings and recall them at the push of a button. That would certainly help the FoH engineer to manage all the acts on one festival bill! The reason this is possible is not just software control, but because most of the physical controllers are switches or rotaries that have no actual 'position'. The illuminated displays tell you if a switch is on or off, or where the Pan is set.

3. Networked. For the most part, here in the IT world, there are two types of data the mixing desk can be exchanging with other devices on the network: a) streaming audio, b) control of other devices' parameters. That means our old multicore can be replaced by a fibre-optic cable, and we can use can use the controls on the desk to adjust remote amplifier levels etc.

Three concepts that are especially useful in this 'new world' of digital mixing:

1. Assignable. Where we used to have a set of EQ knobs on every channel, it makes more sense in the digital domain to have one really nicely laid-out and versatile EQ section that you can assign to any channel. (Once we are up and running with this idea, there is no reason why all the input channel faders can't switch to being the graphic controllers for the system EQ, but let's blow our minds one step at a time!)

2. Automated. There is no reason we can't store a 'snapshot' of all the mixer settings and recall them at the push of a button. That would certainly help the FoH engineer to manage all the acts on one festival bill! The reason this is possible is not just software control, but because most of the physical controllers are switches or rotaries that have no actual 'position'. The illuminated displays tell you if a switch is on or off, or where the Pan is set.

3. Networked. For the most part, here in the IT world, there are two types of data the mixing desk can be exchanging with other devices on the network: a) streaming audio, b) control of other devices' parameters. That means our old multicore can be replaced by a fibre-optic cable, and we can use can use the controls on the desk to adjust remote amplifier levels etc.

simoncroft

Well-Known Member

Into The Digital Domain

At first glance, the mixer below might look a bit basic because it's not the usual row-after-row of rotaries and switches, but the Soundcraft Si Impact Console is a mighty powerful engine under the hood. Depending how you count the beans, there are 40 channels in there. You might be thinking: “How can that be?”

Well, the Si Series is totally digital, which means the only limits on channel capacity are a) I/O (number of Inputs/Outputs) and b) processor power. As we'll see, this desk has plenty of both, and this is the 'baby' of the Si Series.

I've read the User Manual so you don't have to but if you'd like a copy, you can get it here: Soundcraft Si Impact. There are also plenty of instructional videos on the whole series.

Personally, I find videos great for overview and entertainment, but not so good when I'm trying to retain details. For that reason, I'll walk you through some of the key concepts in a series of posts over the next few days.

BTW: this video is about nine years old now, but it's still a useful start.

NB – The video mentions "VCAs".What's a VCA? It's a Voltage Controlled Amplifier. They were first introduced on big analog consoles as a way of controlling a Group, or Bus, without actually sending the audio through another bunch of electronics. so, if you want all your drums on one master fader, all the vocals on another, you assign them to VCAs instead of to Group faders.

At first glance, the mixer below might look a bit basic because it's not the usual row-after-row of rotaries and switches, but the Soundcraft Si Impact Console is a mighty powerful engine under the hood. Depending how you count the beans, there are 40 channels in there. You might be thinking: “How can that be?”

Well, the Si Series is totally digital, which means the only limits on channel capacity are a) I/O (number of Inputs/Outputs) and b) processor power. As we'll see, this desk has plenty of both, and this is the 'baby' of the Si Series.

I've read the User Manual so you don't have to but if you'd like a copy, you can get it here: Soundcraft Si Impact. There are also plenty of instructional videos on the whole series.

Personally, I find videos great for overview and entertainment, but not so good when I'm trying to retain details. For that reason, I'll walk you through some of the key concepts in a series of posts over the next few days.

BTW: this video is about nine years old now, but it's still a useful start.

NB – The video mentions "VCAs".What's a VCA? It's a Voltage Controlled Amplifier. They were first introduced on big analog consoles as a way of controlling a Group, or Bus, without actually sending the audio through another bunch of electronics. so, if you want all your drums on one master fader, all the vocals on another, you assign them to VCAs instead of to Group faders.