Polars bared

Polar Patterns and SPL Explained

In live sound applications, we tend to use ‘directional’, or ‘unidirectional’ microphones almost exclusively. To put it as simply as possible, these are mics that pick up loudest from the front, less at the sides and hardly at all from the back. This is how it is possible for singers to stand in front of loud stage monitors without howling feedback (which is exactly what happens when mics pick up the sound from the speakers and then sends it to the amplifier, back through the speakers…)

However, there are inherent limitations to directional microphones, and it is useful to understand what those limitations are. Not only will it help you to use mics more effectively, it will also help you to understand why mics that might look similar on paper can be quite different in real-world use.

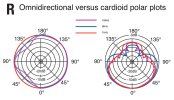

Diagram R contains a lot of information, so let’s go through it a step-at-a-time. First off, what is a ‘polar plot’? It’s a little map that shows you, by points of the compass, how loudly a mic picks up from the front, the sides, the back – and all points in between. For very expensive microphones, the frequency and polar plots supplied are computer-generated readouts of the actual unit you are buying. But for most mics, the plots are generalized descriptions of what the manufacturer is shooting for. Part of what I hope to do in this post is help you to understand how much information you are being given, so you have a better idea of what you’re buying into.

Let’s start by looking only at the red lines, which represent measurements made at a frequency of 1kHz. The mic on the left has a perfectly circular plot at 1kHz, which tells us that it picks up at the same volume level all the way round. (Think of this as a perfect sphere, rather than a circle, because the 2D plot is actually giving us information about what’s happening in 3D space.) A microphone that has this pick-up characteristic is called ‘omnidirectional’.

The mic on the right has a plot that shows far less pick-up to the sides and the back than at the front. This tells us that the microphone is to some extent directional. The most common type of directional mic is called ‘cardioid’, because the plot looks somewhat heart shaped. However, ‘cardioid’ is not one absolute standard. There are ‘wide’ cardioids, ‘tight’ cardioids, and as I’ll attempt to show you, cardioids that are plain all over the place!

Very often, when you go to buy a mic, the manufacturer has placed a handy graphic on the packaging that looks very like the red-line plots we’ve just been examining. While this is useful for telling you that one mic is omnidirectional and another is cardioid, it is nothing like the full story about how a mic really performs. To get closer to the truth about how a mic performs in real life, you have to take measurements at a number of different frequencies. In Diagram R, these are represented by a blue line for 8kHz and a purple line for 16kHz.

The first thing I’m sure you’ll notice is that these new measurements are nothing like as regular as those snappy graphics we got at 1kHz. Looking at the omnidirectional example on the left, the performance isn’t too bad, with -10dB at a couple of points by the time we get to 16kHz. Most omnis will exhibit something like this, and the most likely culprit is the way the capsule is physically mounted, the mass of the casing etc. We might use a microphone like this to record a piano in a concert hall and we would not have to sorry that reflected sound from the room was colored unduly by the mic.

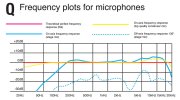

The plot on the right tells a different story, in that the curves at 8kHz and 16kHz are markedly different than the one at 1kHz. To better understand the problems this presents us with, you might want to go back to Diagram Q, which shows a typical frequency plot for a stage vocal mic (solid blue line). As I suggested in the previous post, that on-axis response is very usable.

But look at the frequency response shown by the dotted blue line, which represents the same mic but 135° off axis. Would you want a mic curve like that? Well, bad luck fella, because the chances are you are already using one that performs like that, or even worse. I’ve already flagged this up in previous the thread I started on venue acoustics but I’ll say it again here: the off-axis frequency responses shown in Diagrams Q & R are typical of some of the best vocal stage mics out there. The inherent limitations of directional microphones have to be worked round and cannot be solved simply by throwing more money at the problem.

NB – It is worth pointing out that cheaper stage mics will not even achieve this level of performance. Those are the mics that usually come with only a single idealized plot, based on a single frequency. While it is not impossible to get good results from cheaper mics, you will need more skill and ingenuity. At the other end of the scale, really up-market mics often come with a split polar plot, showing maybe two frequencies per side. This is simply to make the plots for each frequency easier to read. The guys who make those mics aren’t trying to hide anything – they’re showing off.

If the off-axis response of cardioid mics is so irregular, what can be done to minimize the coloration this will cause? The single most successful solution is to keep on-stage volume levels in check, so that mics are not picking up unintended sounds off-axis. It’s worth considering that in many situations, a loud on-stage amp will be picked up by multiple mics, all at different degrees off axis and all at different distances from the sound source. The affect on sound quality can only be negative.

It also helps to use close miking techniques, but this can cause problems of its own if done to excess. For instance, two microphones used as a ‘stereo pair’ a few feet above a grand piano can give a balanced impression of the instrument. The closer the microphones are placed, the more they will focus on particular ranges of the instrument. In theory, you could address the problem by adding more and more mics, but the result is likely to sound less and less like the instrument you are attempting to amplify.

Similarly, if you get in closer to brass instruments than about a yard (1m), you are no longer picking up the sound these instruments make in a room, due to the way in which the lower frequencies radiate from the bell. A similar situation exists with brasswind (woodwind). There is a further sting in the tail, which I’ll explain in a minute.

Another approach is to use more directional microphones. As mentioned earlier, some cardioids are ‘tighter’ than others. There is also a ‘hypercardioid’ pattern that picks up even less from the sides than a cardioid but it’s not a free lunch. The tighter the pattern gets at the sides, the more pronounced the ‘lobe’ around 180° becomes. (You can see this on a cardioid as well, if you look again at Diagram R.) So, although a hypercardioid mic can reduce spill, it can also increase feedback problems if there is a monitor wedge facing directly at the performer.

Now then, if you’ve ever cupped a hand over a stage mic, you’ll know how easily that simple action can push a mic into feedback. That’s because you’ve modified the polar response of the mic by mechanical means. Imagine what happens if you cup an entire trombone bell over a mic! Yep, and if you are using a hypercardioid mic, that lobe gets so much bigger as that bell looms over the mic…

This is an appropriate point to introduce the concept of SPL (Sound Pressure Level). As well as being a useful way of describing the sound level from a rig, or the volume from any sound source, its also important when deciding if a particular mic is ‘up to the job’.

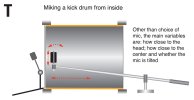

If you’ve ever had your head in a bass drum when the beater connects with the head, you probably didn’t emerge muttering: “I reckon you’ve just unleashed anything in the region of 140dB on my unprotected ears. How interesting.” Similarly, if you’re walking towards a trumpet player, it’s likely you’ll think “jeez that’s loud”, rather than: “When I was four yards away the SPL was in the 96dB region but now I’m only a foot away it must be in excess 130dB.” Far more likely you shouted: “Hey fella! You could turn me deaf doing that!”

Well, mics have a point where they can either be damaged by the incoming SPL, or start to distort. Hence for percussion and brass especially, it is very useful to know whether the mic you intend to use can withstand the kind of SPL you are about to inflict on it.

Next time, I’ll introduce some typical microphone design types (dynamics and condensers) and see how they compare in terms of SPL, sensitivity and frequency range – all of which are inter-related.