simoncroft

Well-Known Member

This thread includes a lot of material I've put on-line over the years, with the aim of helping musicians – whether recording at home or performing on stage – get the best from whatever environment they find themselves playing in. In addition to looking at how an acoustic space alters the sound we hear, I'll cover topics such as, speaker placement, mic placement, and the maths behind the fact that two speakers in a cabinet don't have the same directional characteristics as a single driver. Most importantly though, I'm happy to answer any questions along the way, or get definitive answers from manufacturers and designers if I don't know the answers.

The origins of this thread are in an observation by the guitar maker Ron Kirn that moving your guitar amp's position in a room, and the characteristics of the room itself were likely to have a much greater effect on guitar tone than factors we guitarists like to get hung up about, like body wood. Ron said: "The reality of the way sound is 'modified' by the environment inwhich it’s produced never enters the discussion either... how aroom, replete with hard surfaces, is just plain gonna sound differ-ent than one with “soft” whatever covering the walls... In the world of esoteric audio, the acoustic treatment of the room typically far exceeds the cost of any single piece of equipment that will be used to generate the sound that will fill the roomonce completed. Yet, in the world of the guitarist, seems guys just don’t have a clue how important the acoustic signature of the room they are playing in is, or, of the sonic influence of many peripheral considerations, that rarely get considered... "

… And so we begin

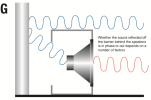

Most of us tend to think of sound arriving at out ears something like Diagram A, a direct transfer of vibrations across the air. In fact, most of what we hear in a room is reflected sound that arrives at our ears only after it has bounced back from one or more solid surfaces. In simplified form, it looks more like Diagram B. (The actual number of reflections will be vastly greater than shown.)

A good experiment to get a feel for the difference that reflectedsound makes is to play an acoustic guitar in the middle of a room. Then sit yourself facing into the corner of the room and keep playing. You’ll find that the closer to the walls you get, the more the tone changes. This effect is known as ‘corner loading’and is thought to be the real reason Robert Johnson recorded while sitting in this position.

I’ll now look at the factors that create the acoustic problems you’ll often encounter in a club or bar, along with what you can do to minimize them.

The origins of this thread are in an observation by the guitar maker Ron Kirn that moving your guitar amp's position in a room, and the characteristics of the room itself were likely to have a much greater effect on guitar tone than factors we guitarists like to get hung up about, like body wood. Ron said: "The reality of the way sound is 'modified' by the environment inwhich it’s produced never enters the discussion either... how aroom, replete with hard surfaces, is just plain gonna sound differ-ent than one with “soft” whatever covering the walls... In the world of esoteric audio, the acoustic treatment of the room typically far exceeds the cost of any single piece of equipment that will be used to generate the sound that will fill the roomonce completed. Yet, in the world of the guitarist, seems guys just don’t have a clue how important the acoustic signature of the room they are playing in is, or, of the sonic influence of many peripheral considerations, that rarely get considered... "

… And so we begin

Most of us tend to think of sound arriving at out ears something like Diagram A, a direct transfer of vibrations across the air. In fact, most of what we hear in a room is reflected sound that arrives at our ears only after it has bounced back from one or more solid surfaces. In simplified form, it looks more like Diagram B. (The actual number of reflections will be vastly greater than shown.)

A good experiment to get a feel for the difference that reflectedsound makes is to play an acoustic guitar in the middle of a room. Then sit yourself facing into the corner of the room and keep playing. You’ll find that the closer to the walls you get, the more the tone changes. This effect is known as ‘corner loading’and is thought to be the real reason Robert Johnson recorded while sitting in this position.

I’ll now look at the factors that create the acoustic problems you’ll often encounter in a club or bar, along with what you can do to minimize them.