Practical strategies for guitarists

OK, enough theory. What can we all – as guitarists who have learned our chops and paid for our gear – do to combat those tone-robbing venue acoustics?

Here is my action list, in approximate order of easy-to-difficult. Some of these solutions only work if there is a full-scale Sound Reinforcement rig. Others are still useful in more intimate gigs, where the speaker in your amp is your only amplification, and any PA is mostly for vocals.

1. Turn down and/or use a smaller amp

As others have suggested earlier in this thread, deafening a small section of the audience at the front from your ‘backline’ amp makes little sense if there is a Sound Reinforcement system that can carry the output of your amp to all of the audience. (This is assuming also there is an on-stage monitor system, so that you can be heard adequately by everyone in the band, regardless of the level from your amp.)

The reasons why some guitarists are reluctant to go down this path vary but they mainly fall into the following categories:

a) I’m a rock star who happens to be playing a small club, therefore I need both stacks set to 11. Solution for problem = grow up emotionally, or get on a stadium tour.

b) My amp doesn’t get the sound I want until it’s running close to flat out. Solutions = buy a smaller amp or a power sink. (I’m sure we all agree there are few sadder sounds than a 100W head with almost no signal going through the power stage or the speakers.)

c) The sound Front of House (FOH) isn’t the sound I’m making on stage. Solutions = test that assumption by getting another band member to go into the venue and see how it sounds and/or get the sound engineer on board with what you actually need. (Good luck with that one if you’re the support act though…)

(In smaller venues, soundmen sometimes lie about whether an amp is miked up at all. When challenged by someone in the audience, they’ll usually say how great the sound balance is the other side of the room.) In general terms: try to get things fixed during the soundcheck so that the you are happy with the FOH sound, but bearing in mind that this will change as the venue fills up.

Also, the sound you are hearing through the stage monitor may be a poor indicator of the sound FOH. While this is annoying, you may have to accept that this is ‘just the way it is’. If the Sound Reinforcement rig isn’t particularly sophisticated, it’s likely that there is no separate ‘system’ EQ for the monitor system. Which brings us to…

d) If I turn down my amp, we can’t hear what I’m playing on stage. Often, the FOH mix guy/gal is also creating the monitor mix(es) going to the stage. Unless you tell them you need more of instrument or vocal X, they’ll assume you’re happy. Solution = communicate with the sound engineer.

An act that has already learned to get a good on-stage balance normally plays better and sounds better than one that relies on the engineer out front to solve all issues. In terms of attitude, this collective approach is the polar opposite to attempting to prove that with

your rig,

you don’t need a FOH system!

2a. Experiment with speaker positioning…

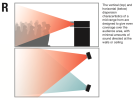

However directional your speaker cabinet is, common sense that the further back it is, the greater area it will cover. (Of course, not all stages are deep enough to give you any choice in this matter.) Similarly, tilting the speaker cabinet in towards the rest of the band may help somewhat in getting even coverage. Diagram Y illustrates these ideas.

… and 2b. Consider sealed versus open-backed cabinets

… and 2b. Consider sealed versus open-backed cabinets

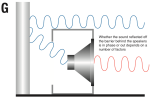

Whether you prefer a closed or open-backed cabinet (or some combination of both) is a matter of personal taste. Arguing which is ‘better’ is as pointless as pitching the same argument about single-coil pickups versus humbuckers. However, it is worth considering the differences between them.

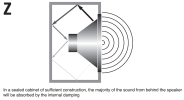

It is often said that the ideal mounting for a loudspeaker would be on a baffle infinitely wide, with an infinite amount of space behind it. This would prevent any out-of-phase signal from behind the speaker interfering with the direct signal from the front of the speaker, which would create a certain amount of cancellation at some frequencies.

A completely sealed cabinet is an attempt to realise this idea by enclosing the space behind the speaker. Providing the cabinet is built solidly enough and is sufficiently damped internally, little or none of the potentially out-of-phase sound can ever mingle with the direct sound from the front of the cone. This is shown in Diagram Z.